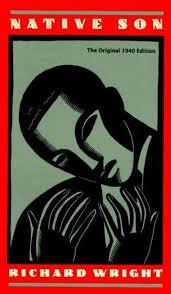

The Difficult Lessons of Richard Wright's Native Son

Lately I've been thinking about Richard Wright's famous protest novel, Native Son (1940). The book is a page-turner like no other, and there is much to learn from it during this long season of exhibitionistic murders.

Wright's Chicago-born African American protagonist, Bigger Thomas, is the native son in question. From the very first pages, he is a criminal in the making: young, brooding, physically powerful, horrifyingly poor, inclined to rob rather than earn, and marginalized in all ways due to his race. Though he is ignorant and unenlightened, a furtive intelligence peeks out from behind his inarticulate rage and despair. He is capable of having ideas, very bad ones.

He can't catch a break, and it's obvious he never will. When he's offered a job as chauffeur for the wealthy white Dalton family, there appears to be a glimmer of respectability in the offing, but you know Bigger will mess things up somehow.

For those who haven't read the book, I'll tread lightly over the particulars. Suffice it to say that Bigger accidentally commits a terrible deed. He compounds it in his macabre attempt at a coverup, and then deliberately commits further heinous crimes. Once the manhunt is on, the press inflames the whole city with racist falsehoods. Bigger is finally caught in a cinematic showdown with the cops, his black body flung against the Chicago snow.

For all of the book's riveting dramatic action, it is the understated final conversation between Bigger and his lawyer, a Jewish Communist named Boris Max, that I keep thinking about. They are coming at this meeting from very different points of view. Max is tense and sad; Bigger is eerily equanimous. Max has come to comfort Bigger and say goodbye; Bigger has figured things out on his own and needs to talk, perhaps even comfort Max.

It turns out he listened very carefully to Max's lengthy and high-minded courtroom presentation, a spirited defense that had everything to do with abstract sociology and little to do with the individual defendant. He has concluded that Max was correct: he is the inevitable and unfortunate product of a racist city and racist society and therefore, by Bigger's own reckoning, not to blame for anything whatsoever.

Going still further, he has decided his actions--the killings--were good. They were the right thing to do. He's figured out a way to justify himself and become his own hero.

"What I killed for must've been good!" Bigger's voice was full of frenzied anguish. "It must have been good! When a man kills, it's for something. ... I didn't know I was really alive in this world until I felt things hard enough to kill for 'em."

Isn't this wild? Isn't this familiar?

The killer in Orlando and the killer in Dallas are our very own Bigger Thomases: angry, hopeless, desperate young men who found a sick justification for their actions. They are entirely to blame for what they did: like Bigger's, their actions are indefensible. Yet we need to look at our society--our nation bulging with firearms and boiling with racial, ethnic, and religious tensions--when we contemplate how these modern-day Biggers came into being. With Native Son as a point of reference, they can be seen in the context of conditions that make them not just possible but terrifyingly likely.

Native Son is not a didactic screed but rather a classic example of literary realism with naturalist flourishes. It invites us to look, see, and think. We don't need to read far into it to notice that Bigger is hardly the only native son gone berserk. In memorably lurid detail, the novel illustrates exactly how racism dehumanizes oppressors and victims alike. The virulently racist white policemen, the rabid white prosecutor, and the race-baiting press all behave in unconscionable ways. Their actions cause us to feel, at times, a modicum of sympathy for Bigger and prevent us from dismissing him as a mere sociopath.

Think, now, of the murderous white overseers of enslaved Americans, the KKK members who lynched black men and women for decades after the Civil War, and last year's white murderer of black churchgoers in Charleston--native sons, one and all. They are on the opposite side from Bigger, but no less demented in their perverted self-justification of their deeds. This is racism in America: everybody suffers, everybody loses.

Native Son is not light summer reading, but 2016 has not given us a light summer. We need to read and reread this book. Its truths are entirely relevant to our time.