Poetry Readings: A Love Story

As an audience member, I approach poetry readings with mingled feelings of hope and dread. These occasions can be truly marvelous or unspeakably awful.

If a poetry reading has any hope of success, certain rules must be observed. The introduction must be brief and free of blather. The poet must be sober and mindful of the clock. The audience, too, must do its part: it should be unplugged, properly fed and caffeinated, and savvy enough not to clap after every darned poem.

If a reading is awful, it is, of course, the poet's fault. The poet has talked too long between poems, used the ridiculous, sing-song "poet voice," or announced at the beginning, "You can hear me without the microphone, right?" The people in the back want to scream: Use it! Use it! Use it! It's not there just to look pretty! But there's always some knucklehead in the second row who nods obligingly, and the dumb-show begins.

A good reading remains a tantalizing possibility. It's sort of like birdwatching: when you see and hear an actual fire-veined poet in the flesh, your heart does backflips. You thank the stars you showed up. You are not blinking, and when you get home, you pace around for a while before you can settle down.

Of the countless readings I've attended over the years, these three poets stand out as the real deal:

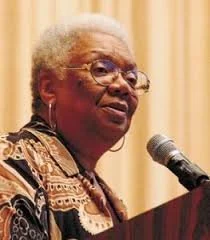

Lucille Clifton

Lucille Clifton, reading in her adopted hometown of Columbia, Md., in the early 2000s. Clifton, who died in 2010, was the rare poet who left audiences wanting more. On this occasion, she was on stage for no longer than 30 minutes, her half of a two-poet reading. Her poem based on the molestation she experienced as a young girl elicited gasps from the audience. It was not a slam poet's self-indulgent shock poem; it was "moonchild," a heartrending study in restraint, published in Blessing the Boats: New and Selected Poems, 1988-2000. When she closed with "won't you celebrate with me," she changed the pronouns so her signature poem about an individual woman's survival against the odds became a communal celebration of endurance. I was not the only one who wept. Clifton had that much grace, that much power.

Louise Glück

Louise Glück, reading at the University of Virginia in 1980 or 1981. The packed auditorium fell into rapt silence as soon as Glück opened her mouth. Slim and elegant in a black dress, she read her poems, many from The House on Marshland, without a word of commentary. You didn't have to be Helen Vendler to know this was a poet headed toward greatness. Glück, whose very cool umlauted name means "luck" in German, is a brilliant presence on stage.

Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks, reading at the Cambridge (Mass.) Public Library, in the late 1990s. The reading took place in a cramped space with not enough folding chairs for all the people who wanted to hear the eighty-year-old poet and leading voice in the Black Arts Movement. Tall and commanding and wearing a colorful turban, Brooks read beneath the glaring light of a local community-access TV station. She read old poems and newer ones, some in sonnet form and some in free verse. With perspiration trickling down her face, she was as fully alive and present in the moment as anyone I've ever seen. She died in 2000. When I close my eyes, I can still hear the applause rocking the Cambridge library as she took her final bow.